Cel Overberghe’s archive

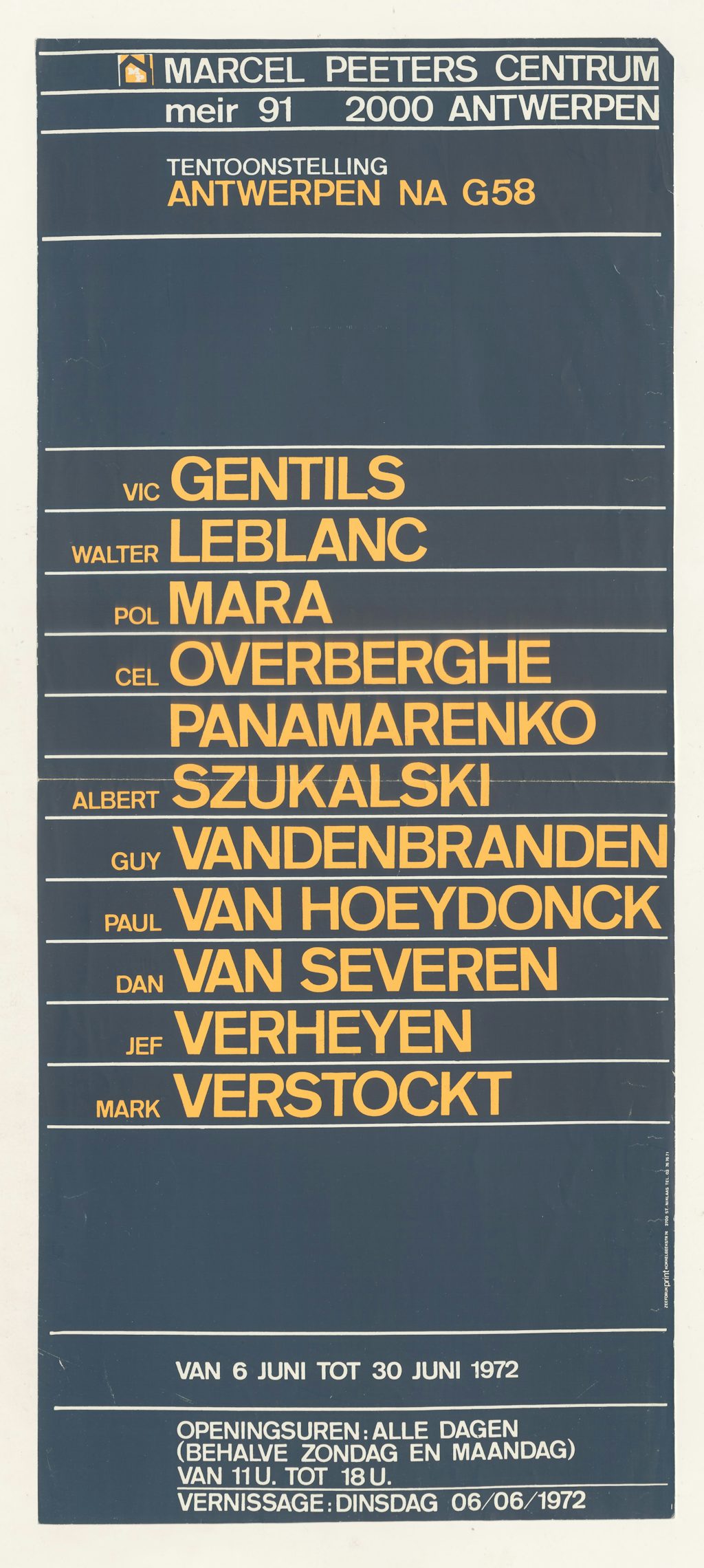

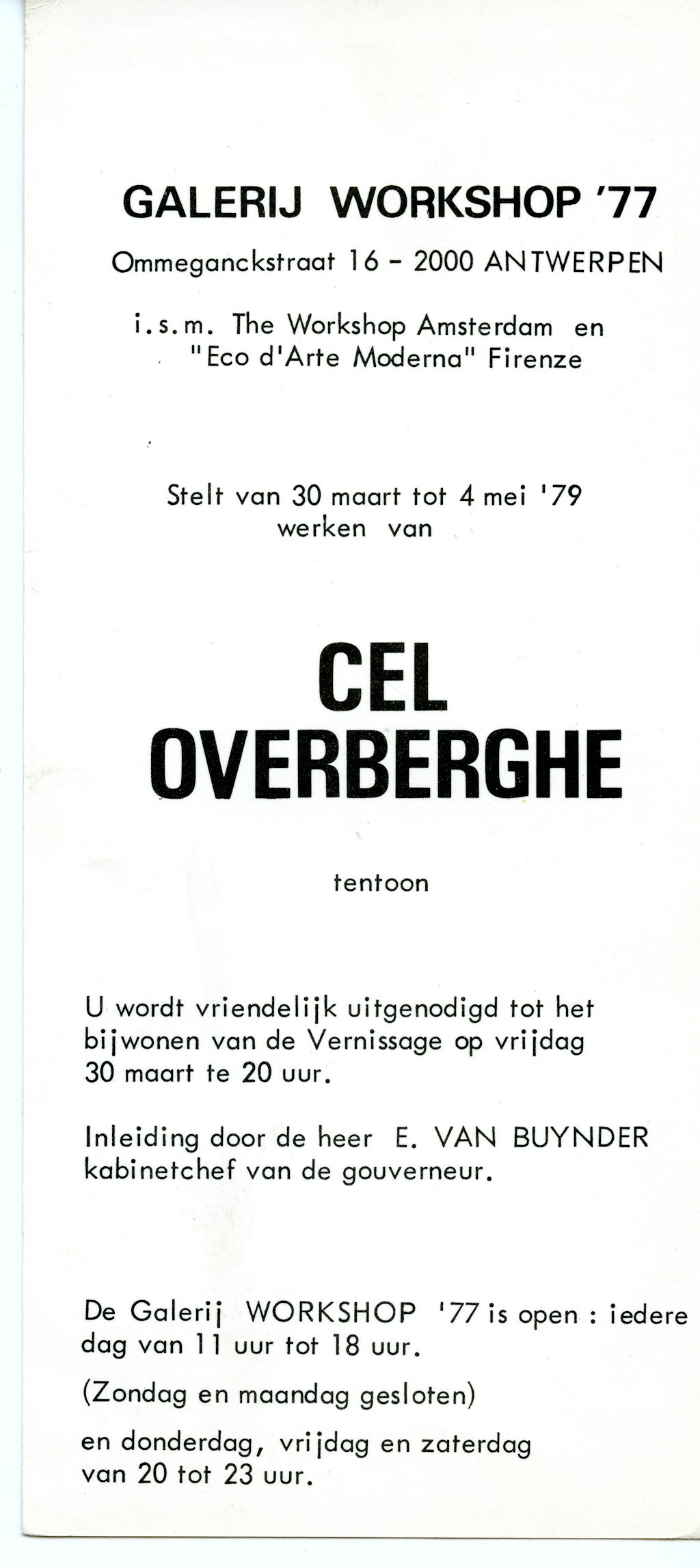

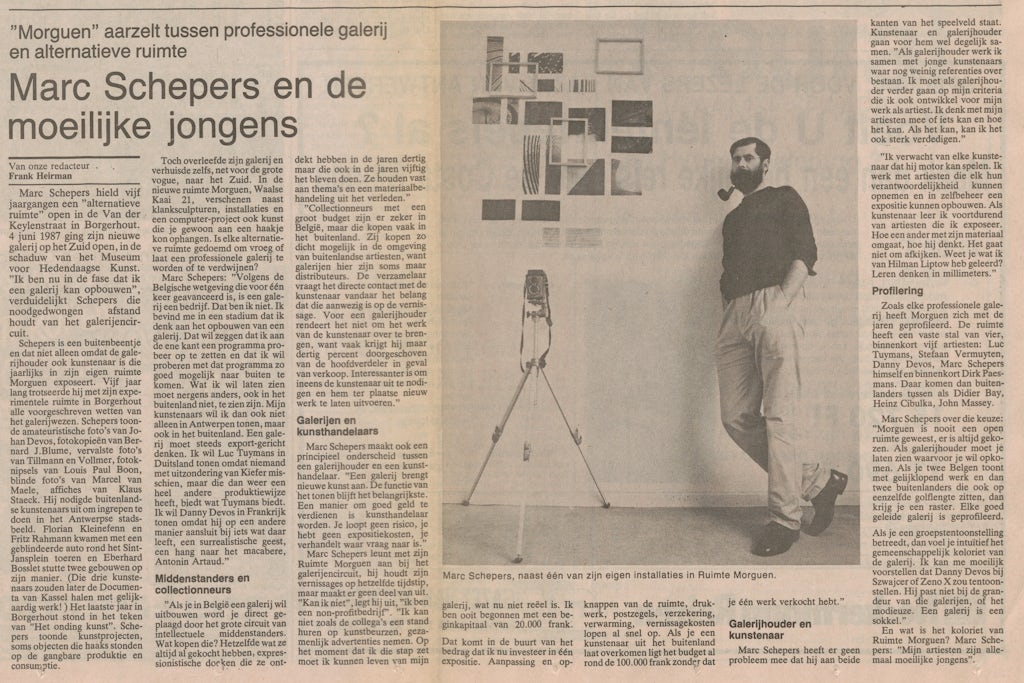

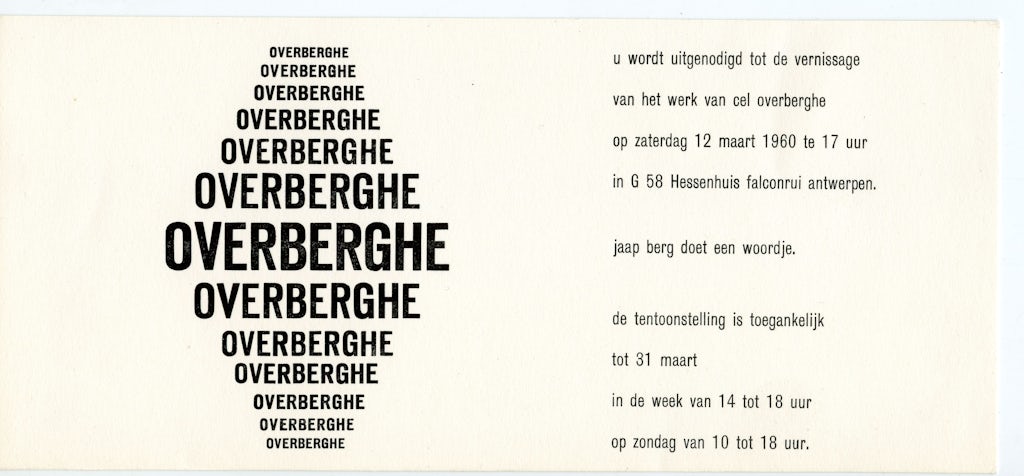

Last spring, bachelor student in art history and archaeology at the V.U.B. Lisa Dierickx did an internship at the Centrum Kunstarchieven Vlaanderen (CKV). Her assignment was to make the archive of artist Cel Overberghe (°1937, Deurne) accessible, step by step. Lisa’s excellent work resulted in a structured inventory and a complete digitisation of the archive and also enabled the colleagues of the CKV to concretise the steps in making an archive accessible. You can find these steps on our website. Instead of a boring description from us, we decided to let Lisa speak for herself on the basis of her internship report. The report below is therefore not only a report on opening up an archive, but also a testimony of the first experiences with an archive.

We are grateful to Lisa for her achievements and we are very curious what the future will bring for this talented (future) researcher.

Lisa Dierickx aan de slag met het archief van Cel Overberghe in M HKA (Foto: CKV)

The Cel Overberghe archive, report by Lisa Dierickx

For my internship at Centrum Kunstarchieven Vlaanderen, I started working with Cel Overberghe’s archive. I have had the pleasure of being able to fully process the archive. Below is a description of the process.

The first step in processing an archive is making an inventory. This means that an inventory is drawn up in Word [or Excel] in which archive documents are inventoried per theme. Each archive item that is inventoried is assigned a number. The first archive item is numbered 1, the second numbered 2, and so on. This numbering is applied both to the inventory and to the acid-free folder in which the archive item will be kept. The folder is acid-free so that the archive item can be optimally preserved.

For each archive item, all important available information is: date, year, title, place, author and type of archive item (all as exact as possible) E.g. ‘bindings’, ‘items’ and ‘cover’.

When the entire archive has been inventoried, the second step is to sort out the archive. The next step is to renumber the archive. Definitive numbering makes it easier to search for an archive item in the archive depot. When that is done, the folders are put in boxes. The number of the first and last archive item inside the box is noted on these boxes. This way, the researcher does not have to open all the boxes in search of an archive item. In a final phase, the researcher only receives the documents relevant to him or her.

The last step in the process is digitising the archive. A folder is created for each archive item. These folders are given a number that corresponds to the archive item. For example, an inventory of digitised archives is made that corresponds to the inventory made in Word.

Foto: ©Luc Van Tichel

As a student at the Center for Art Archives Flanders (CKV)

From the very beginning I had the feeling that my colleagues at Centrum Kunstarchieven Vlaanderen had confidence in me. With every step I took, I never felt that they were looking over my shoulder. This made me feel very comfortable.

When a task was given, it was clearly explained. Whenever I had a question, it was answered completely and concretely so that I could move on immediately. If something had to be shown, it was done in a clear way.

I had never worked in an archive before. As a result, I had no idea how to get started or what the rules were for processing an archive. At the start, everything was calmly discussed, so that I already had a more concrete idea of what my tasks were. This made me feel more confident. After that, space was given to sort everything out and to make mistakes. I think this is very important during internships. Internships exist to familiarise yourself with a field and to learn from mistakes you make.

Centrum Kunstarchieven Vlaanderen is an excellent internship organisation. You get tasks that are at your level and the colleagues are very friendly and always ready to help you.

LD