The Museum as Public Space: Symposium on Archiving Performance Art

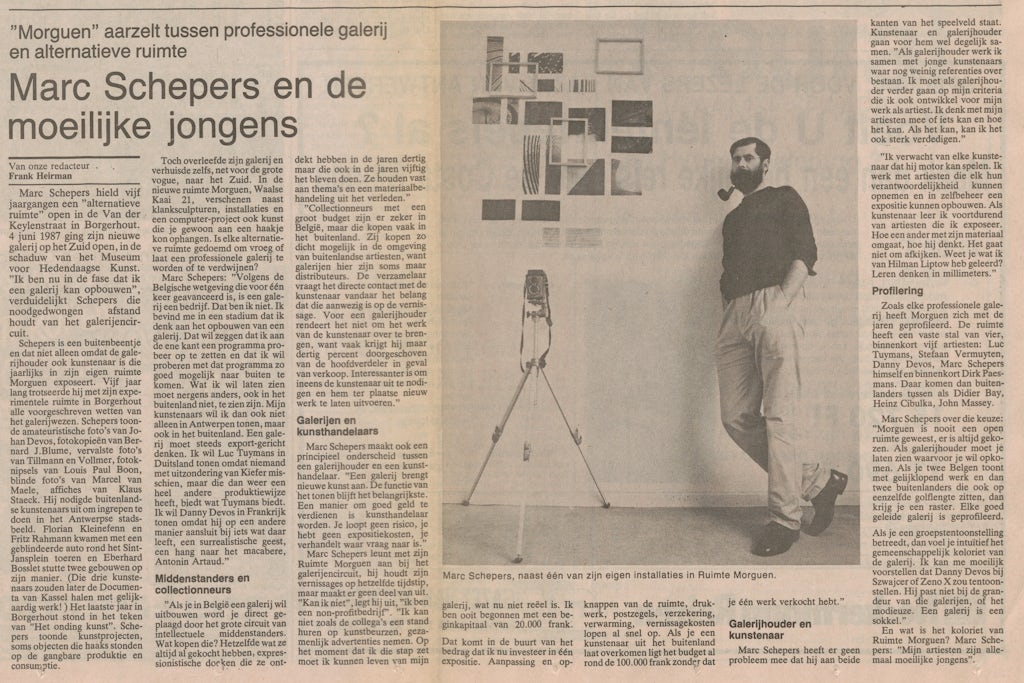

Professionals from the museum and heritage sector, collectors, students and academics attended the symposium. Photo: Bram Goots (2022).

How to archive performance, an art form in which bodies share time and space? This is a question that is currently occupying many museums and artists alike. During the symposium ‘Archiving Performance: Between Artistic Poetics and Institutional Policy’, internationally renowned artists, curators, archivists and academics discussed this topic. The conference was organised by the CKV (Centre for Art Archives in Flanders) in cooperation with the Research Centre for Visual Poetics (Faculty of Arts, University of Antwerp).

Panel discussion ‘The Poetics of the Archive’: Sofie Frederix (M HKA), Otobong Nkanga, dr. Agnieszka Sosnowska (Polish Academy of Sciences,) and Chantal Kleinmeulman (Van Abbemuseum). Photo: Bram Goots (2022).

More than ever, contemporary art museums are opening their doors to live performances, not only in their exhibitions but also in their own collections. Since the 1990s, there has been a growing awareness that institutions have long neglected performance art, resulting in large gaps in their collections. ‘The practice of collecting is a way of writing history, so if we are missing important [performance] practices we are actually writing a different kind of history,’ says Joanna Zielińska, Senior Curator at M HKA. According to her, performance art brings new qualities to institutions because it focuses on relationships, imagination, emotions and experiences; similarly, it also allows us to think about basic concepts such as: what is an object? What is an artwork? Who is the audience and what is its role? In short, performance is an essential part of our museum collections.

A multitude of methods

Performance consists largely of embodied knowledge, and this is precisely what makes it so difficult to document. One method that addresses this to some extent is the artist interview. Chantal Kleinmeulman points out during the panel discussion on ‘The Poetics of the Archive’ that she and her colleagues at the Van Abbemuseum in Eindhoven use this particular method. Artist Otobong Nkanga draws attention to the fact that many artists, including her, change both their thoughts and mindset throughout their careers, which means that, in principle, several artist interviews would be necessary over time to capture this evolution. Her remark is in line with the way she looks at the archive: as a breathing entity, one that requires oxygen and that continues to evolve over time.

Panel discussion ‘The Politics of Acquiring Performance’: Lotte Bode (CKV), Katya Ev, Louise Lawson (Tate) and Dr. Toni Sant (University of Salford). Photo: Bram Goots (2022).

A second and popular method of documenting performance is the protocol: a script that stipulates certain actions and operations in the performance, while simultaneously leaving room for change or personal interpretation. In the panel discussion on ‘The Poetics of the Archive’, artist Katya Ev talked about the challenges she experiences in drawing up a protocol and an archive for her performance Augenmusik (2016). The work is site-specific and is accompanied by attributes, photos or other performances that are related to the work but also have a separate artistic status in their own right. Louise Lawson, curator of time-based media at Tate in the UK, talks about the strategy she developed with her team to conserve and document performance-based art. Every performance purchased by Tate is subsequently re-enacted. Using various documentation tools, Lawson and her team map out which aspects of a performance are changeable, and which are not, within the parameters of the artwork.

Panel discussion 'The Artist's Archive as a Collective Endeavour': Seppe Baeyens and Martha Balthazar (Leon vzw), Dr. Annet Dekker (University of Amsterdam), Sezin Romi (SALT). Photo: Bram Goots (2022).

Transferring embodied knowledge from one body to another is much more common in the field of dance than in the field of performance art. In the third and final panel discussion on ‘The Artist’s Archive as a Collective Endeavour’, choreographer Seppe Baeyens and dramaturge Martha Balthazar explored how their shared choreographic practice can relate to the institutional archive, with the added challenge that their work focuses on processes rather than on an end product. In the closing words, Timmy De Laet, professor of theatre and dance at the University of Antwerp, notes that although dance and performance art have a very different history in terms of archiving, there appears to be a great need to look beyond traditional media and to exchange working methods between different artistic disciplines.

The public space

Bart De Baere, general and artistic director of the M HKA, emphasises the role of the museum as a public space, and Professor De Laet concurs. We do not collect performance art for no reason, says De Laet, but because we want to prolong the gesture that performance art makes. That gesture can be either aesthetic or experimental, but very often it is also politically or socially relevant. ‘If we want the museum to be part of the public domain, then we should also ask: what function does it need to fulfil?’ says De Laet. ‘Is it only then about presenting and collecting art objects or is it also about collecting the knowledges or experiences that people can gather from interacting with these objects?’ Archiving performance art means that we ensure that accumulated knowledge is not lost, but can be shared with others.

Some video reports of the symposium can be found online

Want to know more about the CKV & M HKA research trajectory on archiving performances? Check our website.

Joanna Zielińska (M HKA), Bart De Baere (M HKA) and Timmy De Laet (University of Antwerp). Photo: Bram Goots (2022).